Prof. Dr. Diego Acosta is a Professor of European and Migration Law at the University of Bristol, UK.

The Global Compact for Migration is the first inter-governmentally negotiated agreement, prepared under the auspices of the United Nations, holistically and comprehensively covering all dimensions of international migration. Adopted by 152 countries at the UN General Assembly in December 2018, the Compact (GCM) aims to achieve “safe, orderly, and regular migration along the migration cycle” through several commitments enshrined under 23 objectives. As highlighted by various commentators, the GCM primarily intends to facilitate mobility, since it is only when mobility is not actively hindered that safe, orderly, and regular migration may take place.

In this context, Objective 5 stands out as key. It has two main goals: to create additional pathways for regular migration, and to make these pathways more flexible and diverse. This should help to facilitate labor mobility and “decent work” by considering the realities of the labor market. Indeed, a key criticism of migration management relates to the limited availability of legal migration routes despite the reliance of many countries on migrant labor in various economic sectors. Objective 5 proposes the adoption of international and bilateral cooperation arrangements to enhance safe and orderly migration. It offers three examples, without defining them: visa liberalization, labor mobility cooperation frameworks, and free movement regimes (FMRs).

FMRs are regimes established by agreement between two or more states, generally but not exclusively through a binding international treaty or series of treaties, providing for permanent open channels for the legal entry and stay of workers who are nationals of the participating states, and excluding admission quotas or economic needs tests.1 The three mobility pathways described in Objective 5 represent three levels on the free movement spectrum, from the least to the most ‘freeing’, with FMRs constituting the most expansive level of liberalization.

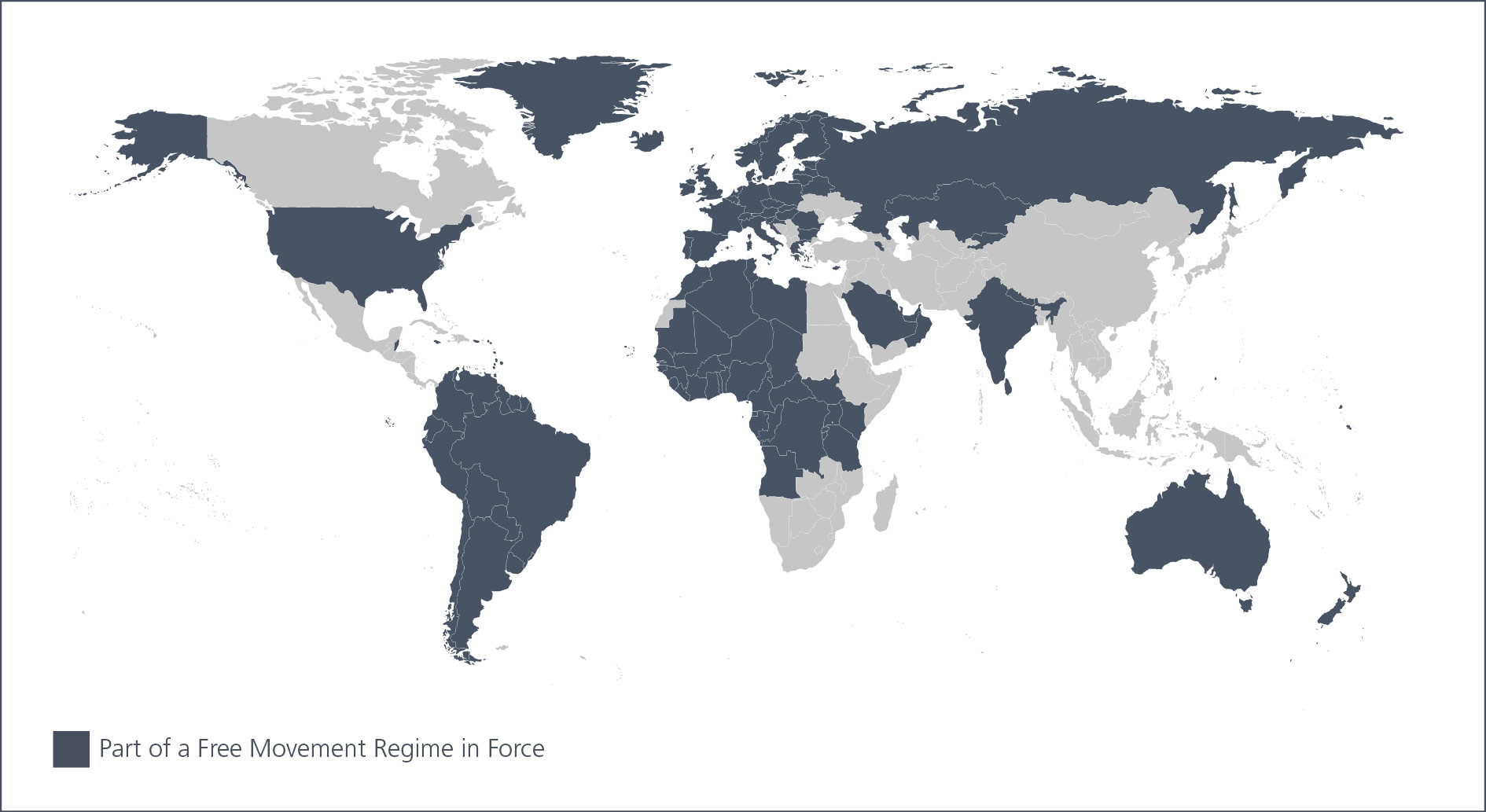

The Free Move project is the first to comprehensively map, analyze, and compare all bilateral and multi-lateral FMRs globally.2 The aim is to identify every FMR in force or adopted between 1992 and 2024 and analyze and compare their provisions. By January 2024, 33 bilateral and 22 multi-lateral regimes had been identified, involving 111 countries across all continents — the majority, therefore, of the 193 UN member states — demonstrating how governments worldwide engage in a variety of treaties to regulate the movement of people, not only by imposing restrictions, but also by facilitating mobility.

Figure 1. Countries worldwide that form part of legally binding FMRs (1 January 2024)

Source: Free Move, 16 September 2024, freemovehub.com

Based on our ongoing analysis, some initial conclusions have been drawn. First, FMRs do not entail open borders.3 Rather, they are legal tools to facilitate the mobility of nationals of participating states, mainly workers. They are not a bonfire of rules on immigration but incorporate numerous standards and processes for filtering and managing migration fluxes.

Essentially, the regimes are built on the paradoxical idea that it is best to manage immigration control by discontinuing certain administrative requirements for nationals of specific regional states. It is important to note that participating states can still deny entry to or deport nationals who do not meet certain conditions. However, the rules for entry, residency, and access to rights are simplified.

Second, FMRs come in a variety of shapes and forms. Some are more comprehensive in terms of the rights and entitlements they offer — for example, the Common Travel Area between Ireland and the UK — while others are more limited — for example, the Caribbean Community (or CARICOM). It would, however, be incorrect to assume that FMRs intend to emulate a European Union model. Instead, it is clear from the data that FMRs greatly influence each other, especially at the regional level. Thus, we can see similarities and the use of a common jargon in FMRs in South America,4 and in Africa,5 both of which present distinctive regional characteristics in terms of how mobility is addressed.

Third, our investigation shows that once countries join an FMR it is very rare for them to denounce the relevant treaty or to terminate it. When FMRs are indeed terminated, as in the case of Argentina–Bolivia or Czech Republic–Slovakia,6 it is usually because an alternative, multi-lateral FMR is in place: namely, MERCOSUR in the case of the former, and the European Union in the case of the latter. The only exception we have identified so far is Cameroon–Mali, where the parties decided to end their FMR outright.7 Of course, when a country leaves a regional organization, as the UK did by withdrawing from the European Union, the free movement of people between that country and the remaining states that are party to the organization comes to an end.

Fourth, FMRs do not necessarily increase migration. The global estimate for international migrants in 2020 was approximately 281 million, accounting for 3.6% of the global population. Interestingly, in the case of the European Union, only 3% of citizens reside in another member state, which is below the global average, despite the existence of free movement in the bloc and the significant differences between member states in terms of unemployment rates, social protection, and average salaries. Poland, for instance, which is the fifth-largest member state by population, had at 1 January 2023 only 32,600 citizens of other European Union member states residing in its territory, representing 0.1% of the total population of the country. To offer another illustration, in Argentina, the percentage of migrants as a total of the population in the country has remained more or less the same for over two decades, that is, 4.2% in 2001 and the same again in 2022, despite the country having the most open and precise implementation of the MERCOSUR Residence Agreements in South America. FMRs do, however, make migration regular, as further exemplified by Argentina, and contribute to making it circular, as shown by several studies.

Finally, FMRs are not immune to the difficulties faced by other international treaties and legal regimes such as compliance, to name but one. It is well known that some of the current, legally binding regimes are plainly ignored by participating countries.8 As studied by some scholars, deficient application in practice is caused by numerous factors such as lack of administrative capacity or poor socialization of the legal norms among key actors, including lawyers, the administration, and judges.9 While the Free Move project does not assess implementation at the domestic level, one of the difficulties with FMRs is a lack of knowledge about, and access to, the key legal instruments composing the regime itself. For this reason, the website allows users to download all relevant legal material in the hope that this will contribute to a better understanding and use of the legal frameworks by all relevant actors, including administrations, lawyers, judges, and other stakeholders.

In conclusion, FMRs have become a normal legal tool in the current migration governance landscape — one that deserves careful attention, scrutiny, and further research.

Notes

1 This definition has been adopted by D. Acosta and J. Martire in ‘The Changing Global Migration Law: Free Movement Regimes and the Creation of the New Migrant’, forthcoming 2025.

2 The dataset can be consulted at freemovehub.com The results for all FMRs in Africa and South America were included by January 2024. Regimes in other regions will be included subsequently. Free Move welcomes comments regarding possible errors in its data, as well as information concerning other possible FMRs.

3 Carens has defined open borders as the idea “that people should normally be free to leave their country of origin and settle in another, subject only to the sorts of constraints that bind current citizens in their new country”. J. H. Carens, ‘Aliens and Citizens: The Case for Open Borders’ (Spring 1987) The Review of Politics (49)2 doi.org/10.1017/S0034670500033817 accessed 10 September 2024

4 See similarities in wording and concepts between Decision 878, Andean Migratory Statute (12 May 2021) Official Gazette of the Andean Community (4239) 1 and Agreement on Residence for Nationals of MERCOSUR State Parties (6 December 2002).

5 See similar approaches in, for example, Protocol on Free Movement of Persons in the IGAD Region, Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD), Khartoum (26 February 2020); and Protocol to the Treaty Establishing the African Economic Community Relating to Free Movement of Persons, Right of Residence and Right of Establishment Addis Ababa (29 January 2018).

6 Convention No. 317/1994 between the Slovak Republic and the Czech Republic epi.sk/zz/1994-317 accessed 2 December 2024

7 Convention Générale d’Établissement et de Circulation des Personnes, Bamako (6 May 1964) derogated by Accord sur la Circulation des Personnes et des Biens, Yaoundé (8 September 2015)

8 See, for example, the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) regime and how it is not implemented as reported by numerous studies: E. Erasmus et al., ‘MME on the Move: A Stocktaking of Migration, Mobility, Employment and Higher Education in Six African Regional Economic Communities’ (January 2013) International Center for Migration Policy Development. icmpd.org/file/download/48315/file/MME.pdf accessed 10 September 2024; T. Wood, ‘The role of free movement of persons agreements in addressing disaster displacement’ (May 2018) Platform on Disaster Displacement disasterdisplacement.org/resource/free-movement-of-persons-africa/ accessed 10 September 2024

9 B. Simmons, Mobilizing for Human Rights International Law in Domestic Politics (Cambridge University Press 2009); R. Howse and R. Teitel, ‘Beyond Compliance: Rethinking Why International Law Really Matters’ (7 May 2010) Global Policy 1(2) onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1758-5899.2010.00035.x accessed 10 September 2024

Prof. Dr. Diego Acosta is Professor of European and Migration Law at the University of Bristol. He is also the Director of the Nebrija-Santander Global Chair of Migration and Human Rights at Nebrija University in Madrid. Prof. Acosta has written over 60 published academic works, including books, edited collections, and papers in academic journals. He has been approached by numerous governments and international organizations for advice on comparative migration and nationality law. These include the European Union, the International Organization for Migration, the Inter-American Development Bank, the African Union, and many more. His current project, Free Move, is funded by the Open Society Foundations, and it includes producing maps, analyses, and the comparison of free movement of people regimes at a global level.

Henley & Partners assists international clients in obtaining residence and citizenship under the respective programs. Contact us to arrange an initial private consultation.

Have one of our qualified advisors contact you today.

We use cookies to give you the best possible experience. Click 'Accept all' to proceed as specified, or click 'Allow selection' to choose the types of cookies you will accept. For more information, please visit our Cookie Policy.