Dr. Juerg Steffen is CEO of Henley & Partners and author of definitive books on high-net-worth relocation to Austria and Switzerland.

Over the past quarter, we have watched countries around the world attempt to find routes to recovery from the effects of the global health emergency. A key path to a return to normality, of course, is the resumption of regular international travel, with many urgent questions still to be addressed: Is a return to pre-pandemic levels possible within the next year? How will this be achieved? Who will surge ahead, and who will be left behind? These questions are perhaps more pressing now than they have been at any other stage of the pandemic.

The latest results and research from the Henley Passport Index — the original ranking of all the world’s passports according to the number of destinations their holders can access without a prior visa — show that while there is cause for optimism, it must be tempered with the reality that international travel continues to be significantly obstructed. The fact is that cross-border travel remains a remote possibility for many, and particularly leisure travel, a sombre prognosis for countries that desperately need tourist traffic over the northern hemisphere’s summer period to assist with their economic recovery.

Although some progress has been made, between January to March 2021 international mobility had been restored to just 12% of pre-pandemic levels in the same period in 2019, and the gulf between theoretical and actual travel access offered even by high-ranking passports remains significant.

As in previous months, temporary pandemic-related visa restrictions have taken precedence over long-term policy agreements between states, which means there have been few shifts in the Henley Passport Index. However, the latest results nevertheless provide interesting insights into what travel freedom means today, 18 months after the pandemic began.

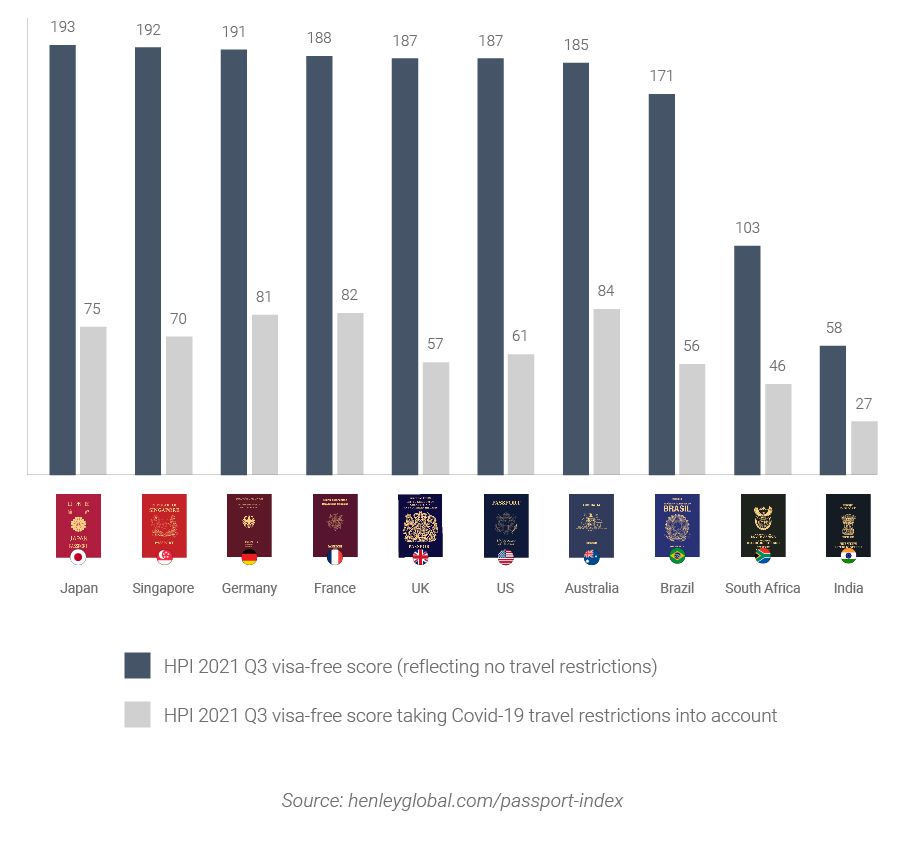

Japan retains its hold on the number one spot on the Henley Passport Index — which is based on exclusive data from the International Air Transport Association (IATA) — with a theoretical visa-free/visa-on-arrival score of 193. While the dominance of European passports in the top 10 has been a given for most of the index’s 16-year history, the pre-eminence of three Asian states — Japan, Singapore, and South Korea — has become the new normal. Singapore remains in 2nd place, with a visa-free/visa-on-arrival score of 192, and South Korea continues to share joint-3rd place with Germany, each with a score of 191.

However, when compared to the actual travel access currently available even to the holders of top-scoring passports, the picture looks very different: holders of Japanese passports have access to fewer than 80 destinations (equivalent to the passport power of Saudi Arabia, which sits way down in 71st place in the ranking) while holders of Singaporean passports can access fewer than 75 destinations (equivalent to the passport power of Kazakhstan, which sits in 74th place).

There is a similarly gloomy outlook even in countries with highly successful Covid-19 vaccine rollouts: the UK and the US currently share joint-7th place on the index, following a steady decline since they held the top spot in 2014, with their passport holders theoretically able to access 187 destinations around the world. Under current travel bans, however, UK passport holders have suffered a dramatic drop of over 70% in their travel freedom, currently able to access fewer than 60 destinations globally — a passport power equivalent to that of Uzbekistan on the Henley Passport Index. US passport holders have seen a 67% decrease in their travel freedom, with access to just 61 destinations worldwide — a passport power equivalent to Rwanda’s on the index.

Despite the uneven progress of vaccine rollouts and the relaxing of inbound travel restrictions, cautiousness will remain the order of the day as governments look to manage the risks associated with the spread of new variants. In the developing world, the slow pace of vaccine rollouts has raised profound concerns about access and inequality and what this means for future global mobility levels, particularly given the fact that developing countries tend to have lower mobility scores and fall towards the bottom of the ranking.

Looking at the current rankings of countries on the African continent for instance, such concerns appear to be well founded. Nigeria, for instance, is in 101st place on the Henley Passport Index, with access to just 46 destinations around the world, and the Democratic Republic of Congo sits in 104th place, with access to only 43 destinations. The vaccine rollouts in both countries have been so limited as to be almost non-existent, and it seems clear that the already record-high global mobility gap between advanced and developing economies will only widen in the months to come.

The gap in travel freedom is now at its largest since the index began in 2006, with Japanese passport holders able to access 167 more destinations than citizens of Afghanistan, which sits at the bottom of the index. Its passport holders are able to visit only 26 destinations worldwide without acquiring a visa in advance.

As they have done for much of the Henley Passport Index’s 16-year history, countries offering residence- and citizenship-by-investment programs continue to perform strongly. Malta, for instance, remains in 8th place, with passport holders able to access 186 destinations around the world notwithstanding any Covid-related travel bans. Austria remains in 5th place, with a visa-free/visa on arrival score of 189, and Portugal (6th on the ranking with a score of 188) and Montenegro (47th on the ranking with a score of 124) have also consistently performed well.

Looking at longer-term movements in the rankings, the rise of the St. Lucia passport provides a prime example of the mounting passport strength of countries that offer investment migration programs. Over the past 10 years, the Caribbean island nation has climbed 17 places in the ranking, making it one of the highest climbers of the decade.

The relentless volatility that has so far characterized this decade means that diversifying country risk has become a priority in terms of personal access rights as well as financial and property investment. Even high-net-worth individuals from advanced economies with premium passports and world-class healthcare systems are now looking to create portfolios of complementary citizenship and residence options. They all share the same intention — to access health security and optionality in terms of where they can live, conduct business, study, and invest, for themselves and their families.