Prof. Trevor Williams is the former Chief Economist at Lloyds Bank Commercial banking, a position which he held for over ten years. He now runs a consultancy specializing in economic analysis encompassing ‘big data’ to understand better a fast-changing global economy and its political context, namely, its political economy.

Global wealth has risen from about USD 150 trillion to around USD 500 trillion since 2000, and data in the Henley Global Citizens Report 2022 Q2 shows that the global number of high- and ultra-high-net-worth individuals has increased in tandem. On 31 December 2021 there were over 15.3 million high-net-worth individuals with wealth above USD 1 million, 593,340 multi-millionaires with over USD 10 million, 26,670 centi-millionaires with wealth more than USD 100 million, and 2,241 US dollar billionaires. The vast rise in the number of millionaires and billionaires in the last few decades has been driven by four key factors, which are likely to continue to push up the numbers over the decade ahead. While the pace is expected to be slower in traditional wealth markets, emerging economies are forecast to boom.

Since the turn of the 21st century, there has been an enormous increase in global savings. This reflects the increase in global incomes and, therefore, living standards, alongside a decline in poverty. More and more people have enough left over after meeting all their living expenses to put money aside. Consequently, in many countries, more earn enough to own a car, own homes, educate their children, and set money aside for a rainy day, in other words, to save.

But these savings must be deposited somewhere to earn a return for those foregoing spending and deferring it into the future. Therefore, the funds are invested in products or assets. Since savings must equal investment, the latter has also seen massive growth over the last few decades, though not always in physical assets such as plant and machinery.

Savings are translated into business investments in specific business segments such as technology, infrastructure, construction, house building, and in manufacturing and services. Many business owners, service providers, and product inventors have become vastly richer. They form the basis of the increase in millionaires and billionaires represented in the data discussed below, which four key factors have driven.

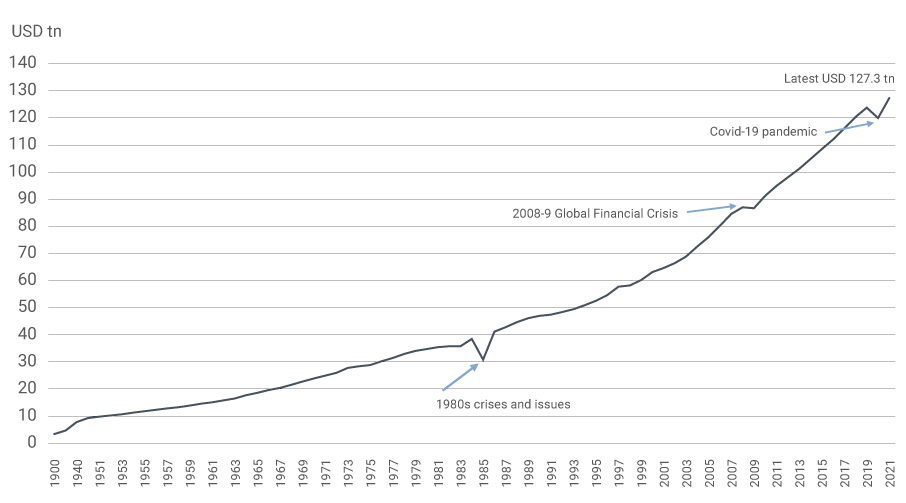

The first factor is the continued rise in global GDP and global living standards. Despite the many challenges that the world economy has faced in the last decade, as Figure 1 illustrates, data clearly shows that the increase in global GDP has continued.

Figure 1. Global GDP since 1900

Note: 2011 prices, adjusted for inflation

Sources: IMF, World Bank, and Maddison (2017)

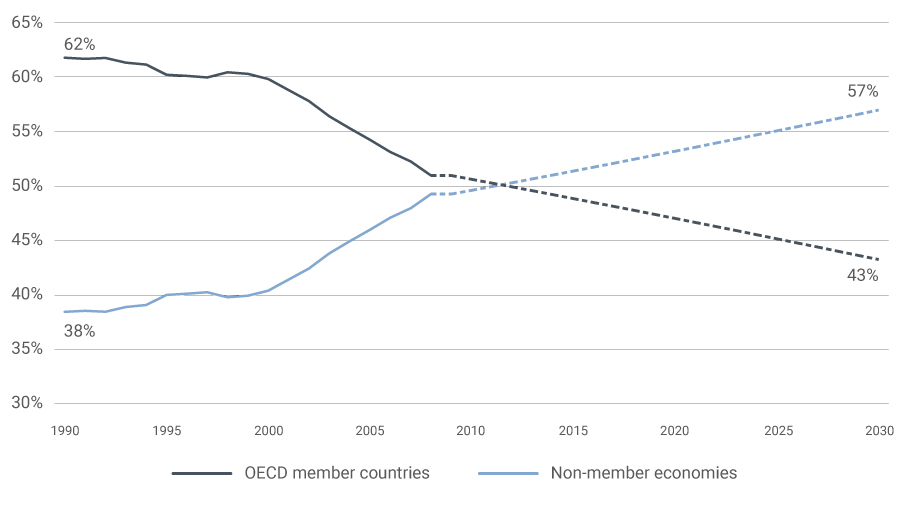

The changing composition of global GDP contributes to the rise in the number of affluent individuals. There’s been a considerable increase in the share of world economic output coming from previously underdeveloped or lower-income economies, as Figure 2 illustrates. Thirty years ago, these countries accounted for only 20% of global GDP — now, they account for 60%.

Figure 2. Share of global GDP shifting to developing countries (GDP in PPP terms)

Note: Dotted lines indicate projections.

Source: Maddison’s long-term growth projections to his historical PPP-based estimates for 29 OECD member countries and 129 non-member economies.

Not surprisingly, given the increase in economic growth, wealth today is also higher relative to GDP than in the past. Of course, wealth is a function of GDP and arises from the excess income created from growth, but it’s also a function of the value of the underlying assets and how those change over time.

World savings have been boosted by the policy responses of governments around the world to the financial crisis of 2007–2009 and, more recently, the pandemic of easing monetary policy. Hence, quantitative easing — injecting liquidity into financial markets by purchasing bonds and other securities — has added USD 25 trillion to global liquidity, with the USA accounting for nearly USD 10 trillion.

Loosening fiscal and monetary policy was done to prevent the economic dislocation created by these crises from having more severe economic contractions than seen. A side effect has been the expansion of the pool of global savings, which has increased the price of assets and so boosted the wealth of holders of these assets.

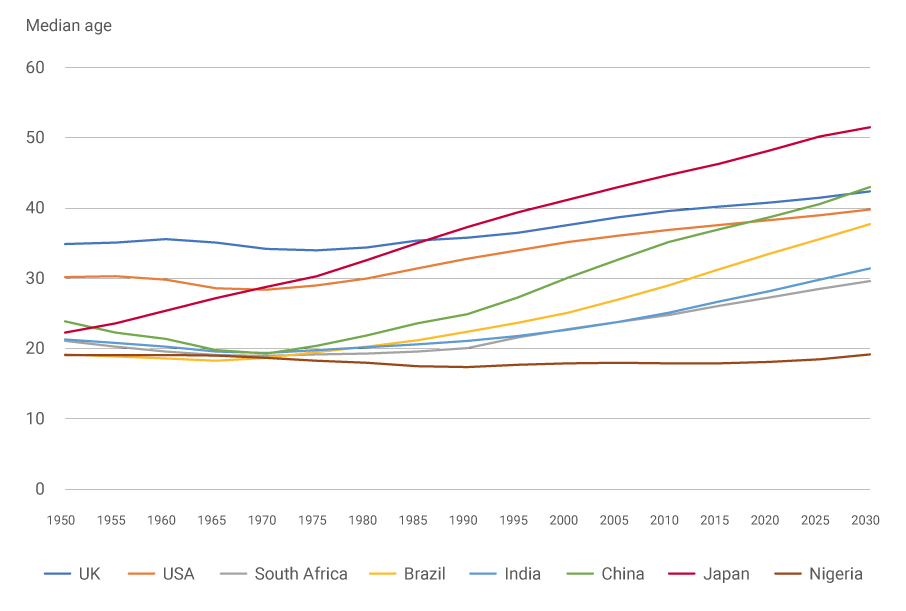

Finally, the world’s population growth is slowing and ageing. As Figure 3 illustrates, the global population has aged since 1950 and will continue to do so rapidly. As populations age, savings increase as more people put money aside for retirement, which means the investable pool of assets rises enormously.

Figure 3. Median age of the population

Sources: UN historical data and projections

Moreover, the composition of the ageing population geographically by country has broadened, even though the majority are still in countries that have traditionally produced the bulk of the world’s billionaires and millionaires. However, the growth of wealth and rising numbers of wealthier individuals are increasingly in countries with large populations seeing faster income growth.

Most forecasts show economic growth over the next 10 years will be fastest in emerging or low-income countries. Population growth will also be fastest in these economies, therefore so will savings. These developments and assumptions underpin the forecast rise in wealth produced in the Henley Global Citizens Report 2022 Q2 — and are well-founded on the evidence.

The data in this report shows that wealth is rising as a share of GDP, so it has grown faster than GDP over the last decade. There is increasing financialization of the economy, as growth in financial assets has risen remarkably quickly owing to quantitative easing.

Wealth is determined by the size of a country’s population, GDP per capita, level of economic development, and openness to international trade and capital flows. All these aspects have improved in low-income and developing economies in the last decade, which means they are well placed to see continued fast-growing wealth over the next decade as they continue to expand.

As the world economy grows, economies in Africa, Latin America, and elsewhere in the Global South are catching up with high-income economies, as Figure 3 indicates. And as the forecast high-net-worth-individual growth data in this report shows, they will see a more significant number of millionaires and billionaires in the next decade. For example, the number of high-net-worth individuals in Sri Lanka is forecast to increase by 90% by 2031, while India and Mauritius’s high-net-worth growth is forecast at 80%, and China’s at 50% compared to 20% in the USA and 10% in France, Germany, Italy, and the UK.

Since tangible assets are critical to the economy’s growth, the residential and commercial property sector will retain the largest share of total wealth, followed by industrials and holdings in stocks and shares and bonds. Of course, industrial machinery equipment too, as well as commodities, are essential ingredients to drive growth. Land and commodities are particularly abundant in many low-income and developing economies that this report has touched on, making their success even more likely as these assets are utilized.